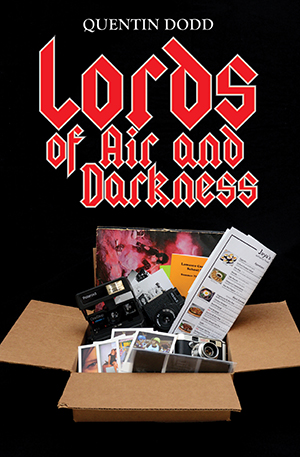

Heavy Metal Horror!

Sixteen year-old Hal Hughes loves three things: his camera, his girlfriend, and heavy metal from the 1980s. Possibly not in that order.

John Graze, a local recluse and former frontman for the legendary band Left Hand Ritual, is Hal’s idol. When Hal learns that Graze has come out of hiding, he’s curious. When Hal finds out that his girlfriend Macie’s high school musical has Graze as an advisor, he’s absolutely mystified.

Hal spies on the former metal god and sees him performing strange, gruesome rituals. With the assistance of an eccentric expert on sorcery, Hal discovers the horrible fate in store for Macie and the rest of the musical cast.

Soon Hal is fighting off warlocks, creatures, medieval re-enactors, and rivals for Macie’s love. Time is running out and John Graze’s magic is getting more powerful by the day. Can Hal stand up to the new master of evil?