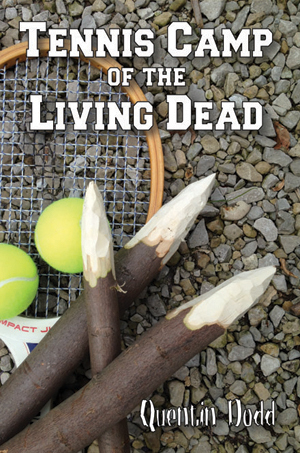

Stickley Smythe is spending the summer at Bright River Tennis Academy. He’s playing against top competition and learning from the best tennis coaches in the country.

But something isn’t quite right.

Everyone else thinks the camp is perfectly normal, but Stickley can’t help asking questions, such as:

Why does the camp pro never go out in the sunlight?

Why are they building coffins in arts and crafts class?

Why do the villagers across the river fear the camp so much?

and, most importantly:

Why did he agree to come here in the first place?

As Stickley works to unravel the mystery, he realizes that he’s staying at no ordinary summer camp.

Instead, he’s stumbled upon the Tennis Camp of the Living Dead!